The site has been sacred since Celtic times and the name Auchinleck is Celtic for ‘field of stones’. It has been a parish since the medieval period with graves dating back to 1643. The Old Church was enlarged to its present size in 1641-3 and remained in use until replaced in the early 1840s by the present Victorian church.

The square Boswell Mausoleum, which adjoins the old church, did not start life as a tomb. It was originally constructed, or, most likely, remodelled from an earlier extension in the mid-1750s by Lord Auchinleck as a two-storeyed Laird’s Loft with a gallery over-looking the congregation, facing the pulpit. On the ground floor was a cosy ‘chamber’ as James Boswell referred to it with its own fireplace, table and chairs. Here the family could retire – or listen by the window to the barn-storming preachers, who attracted congregations too vast for the kirk itself, declaiming from a tented pulpit in the graveyard.

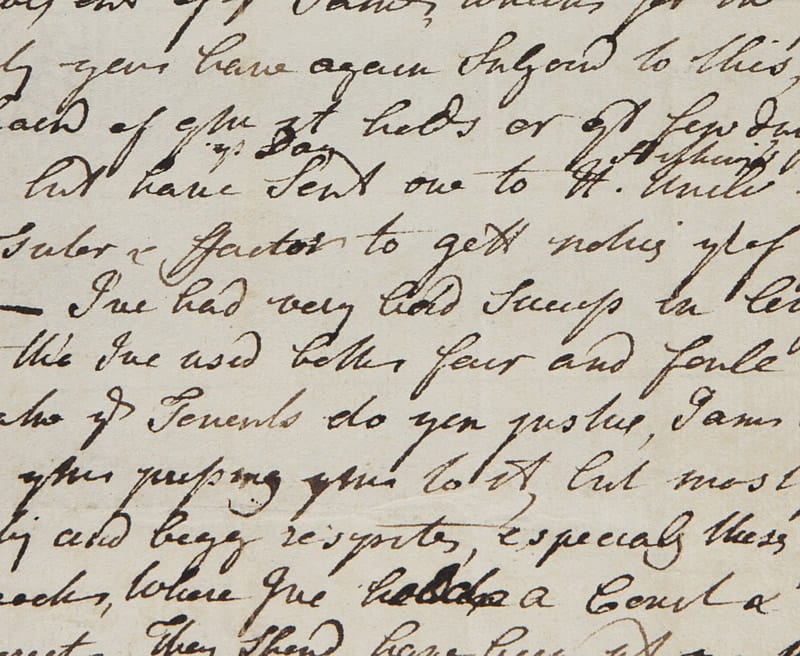

The Loft was not only used by the family. The Kirk Sessions were held there and it was also the place where the Boswell tenantry came to pay their rents. Evidence of the old loft survives in the simple stone fire surround and the blocked up windows on the south wall.

As with Auchinleck House, which was built at the same time, no architect has been identified with this handsome structure, but the guiding hand of Lord Auchinleck is clear. He recorded discussing architecture with his neighbour, the earl of Dumfries, over dinner at Dumfries House. Certainly the Adam brothers’ designs would have been an inspiration for the classically minded Lord Auchinleck.

Beneath the Loft, there was already a columbarium (literally a pigeon house) which served as the resting place for Lord Auchinleck’s mother, who died in 1734, and his father, who died in 1749. It is here that James Boswell now lies, surrounded, as in life, by his father, mother, step-mother, wife, a daughter and son – the dramatis personae who caused him such anguish and love as so unflinchingly recorded in his Journals.

It was some 45 years after Boswell’s interment that the loft was officially turned into the family mausoleum. The cause was the completion of the adjacent Victorian church and the unroofing of the old kirk, which rendered the Laird’s Loft redundant. Again, the architect of the transformation is unknown, but it was a most accomplished exercise, which saw the homely loft transformed into a dignified, neo-classical monument with a stone pyramid roof, topped with funerary urn, and blank walls only relieved by a beautifully carved coat of arms. Three nineteenth century Boswells in their coffins were the only occupants of this remarkable new space. Since then the chamber, to which there is no public access today, has remained virtually untouched. Meanwhile the Old Kirk was re-roofed in the 1970s.

The Boswell associations with Auchinleck and its church and churchyard were close, and spanned several generations, as we learn from The History of Auchinleck: Village and Parish (1991; 2nd edition 2015) by Dane Love. Lord Auchinleck, among other improvements to his estate, the village and its wider access, built the three-mile road, which he called his ‘Via Sacra’ (the ‘Holy Way’ now named the Barony Road), lined handsomely with beech and oak trees, and which runs from the estate to the parish church. After his improvements to the church itself, Lord Auchinleck erected a commodious new two-storey manse. On the death of Boswell’s mother, Lady Auchinleck, in 1766, two silver communion cups were given to the church. When Lord Auchinleck himself died in 1782, his funeral, which his son James Boswell arranged and superintended, “was probably one of the largest seen in the parish, the corpse brought back from Edinburgh for burial in the mausoleum which he had previously erected” (Dane Love). Boswell’s diary movingly records how he himself helped carry his father’s coffin into the vault.

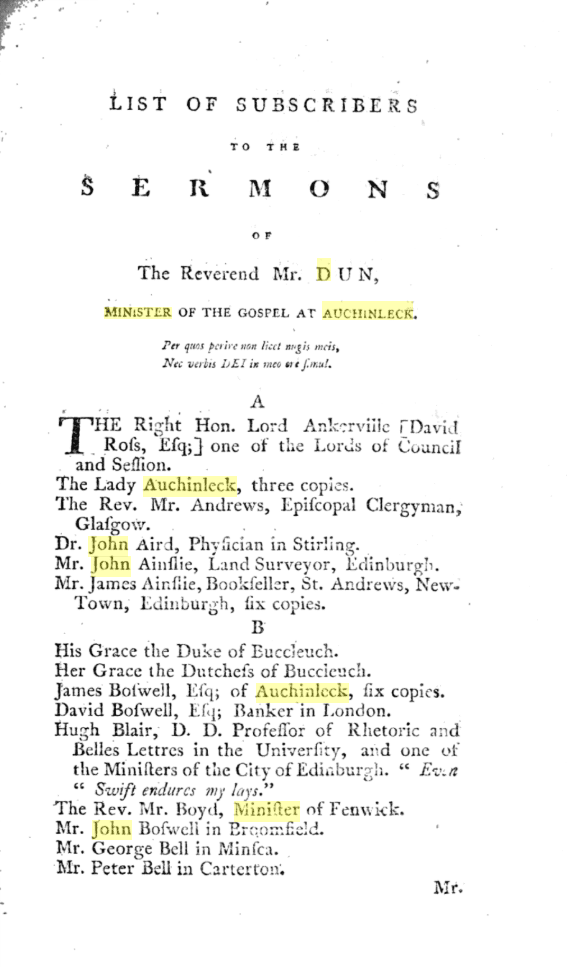

The most important and influential of Boswell’s boyhood tutors was John Dun, whom, on his ordination, Lord Auchinleck presented to the parish of Auchinleck, where he served for 40 years until his death in 1792. Dun was a very able minister, whose sermons Boswell helped see to publication, and he brought a new detail and regularity to the session records and registers of births, deaths and marriages. In 1792, Boswell devoted much serious lairdly care to the choice of Dun’s successor (the Rev. John Lindsay), with more than forty letters on the subject surviving among his correspondence.

When larger congregations required the building of a new church in the late 1830s and early 1840s, during the lairdship of Boswell’s grandson, Sir James Boswell, 2nd Baronet, freestone for the work was obtained from a quarry owned by the Boswells. After Sir James’s death in 1857, his widow, Lady Boswell (formerly Jessie Jane Cuninghame, daughter of the 6th Baronet of Corsehill) continued the family benefactions. ‘She was responsible for having the wall and railings erected around the churchyard, and during her lifetime paid for the upkeep of the grounds within, keeping them “like a garden”. (Dane Love)

In 1894, during extensions and repairs to the church, a window was installed in memory of Lady Jessie (who had died in 1884) with funds raised by public subscription. The window’s scene, which incorporates the Boswell arms and the family motto, is based on a painting called ‘Charity’, by Sir Joshua Reynolds, affording a pleasing historical symmetry: this memorial of generations of Boswell family generosity to the church and parish draws inspiration from a painter who was the biographer James Boswell’s great friend, the man to whom his pathbreaking biography Life of Samuel Johnson was dedicated.